An introduction and guide to my series of posts “Corpora and the Second Amendment” is available here. The corpus data that is discussed can be downloaded here. That link will take you to a shared folder in Dropbox. Important: Use the “Download” button at the top right of the screen.

COFEA and COEME: lawcorpus.byu.edu.

This was supposed to be the final entry in my series of posts on the Second Amendment, but I’ve decided to split the discussion into two parts.

In my last post, I concluded that as used in the Second Amendment, bear arms was most likely understood to mean ‘serve in the militia.’ The question that I’ll address here and in my next post is whether that conclusion is changed by the fact that the Second Amendment protects not simply “the right of the people to bear arms” but “the right of the people to keep and bear arms.”

The corpus data on keep and bear arms is of no help in answering that question, because all the uses of the phrase in the data are either from the Second Amendment or from drafts of proposals for what became the Second Amendment. Therefore, I won’t deal with the corpus data at all in this post, and I’ll deal with only a relative handful of concordance lines in the next one (though those lines will play an important role in the analysis).

Taken together, these two posts will provide an extended rebuttal of the portion of Heller (consisting of only four sentences) that raised the question that these posts will address. Those four sentences were part of the court’s argument that bear arms as used in the Second Amendment couldn’t possibly have been understood in its idiomatic military sense:

[If bear arms were given its idiomatic meaning,] the phrase “keep and bear arms” would be incoherent. The word “Arms” would have two different meanings at once: “weapons” (as the object of “keep”) and (as the object of “bear”) one-half of an idiom. It would be rather like saying “He filled and kicked the bucket” to mean “He filled the bucket and died.” Grotesque.

When I first read Heller, this struck me as a pretty strong argument. But I’ve rethought the issue since then, and have come to think that the argument is seriously flawed. At this point, although I don’t dismiss the argument altogether, I don’t think it rules out interpreting bear arms in the Second Amendment to mean ‘serve in the militia.’

THE PROBLEM WITH the court’s argument isn’t its premise; it’s true that interpreting bear arms in the Second Amendment as an idiom would result in arms having the two meanings that the court refers to. But the conclusions the court draws from that premise aren’t valid. A word that appears only once in a phrase can in fact convey two different meanings, and it can do so without making the phrase incoherent. Moreover, the factors that make filled and kicked the bucket a train wreck aren’t present in keep and bear_armsmilitary.

As evidence that incoherence doesn’t always result from a single use of a word conveying two meanings, I offer the examples below (in some of which, as in filled and kicked the bucket, the Janus-faced word functions both as an ordinary direct object of one verb and as part of an idiom that includes the other verb):

They took the door off its hinges and went through it.

John expired yesterday and so did his driver’s license.

The farmers grew potatoes and bored.

Mr. Pickwick took his hat and his leave. (Dickens, The Pickwick Papers.)

Miss Bolo rose from the table considerably agitated, and went straight home, in a flood of tears, and a sedan-chair. (Dickens, The Pickwick Papers.)

By the time we left the bar, I’d bought him three drinks as well as his argument.

He drowned his cat and his sorrows.

This is the city of broken windows and dreams.

The addict kicked the habit and then the bucket.

[The uncredited examples are taken (or adapted) from Cruse, Lexical Semantics (1986) (link), and Solska, “Accessing multiple meanings: The case of zeugma” (pdf).]

Although none of these examples are incoherent, they all come across like puns. That phenomenon is known as ZEUGMA. But not all cases of a single use of word conveying two meanings are zeugmatic. If the two meanings are related to one another, the sense of oddness that is felt in cases of zeugma can be absent:

The red book on my nightstand is really interesting.

red book on my nightstand (book as physical object)

book…is really interesting (book as text)

The bank on the corner just fired all its tellers.

bank on the corner (bank as building or premises in building)

bank … fired all its tellers (bank as employer and financial institution)

The door was smashed in so often that it had to be bricked up. [from Cruse.]

door was smashed in so often (door as the part that opens and closes)

door had to be bricked up (door as doorway)

[Update: I’ve modified the first of these examples to try to avoid a possible complication raised by a comment to me.]

The phenomenon at work in the previous three examples is often referred to in the linguistics literature as CO-PREDICATION.

Although co-predication differs from zeugma only in that co-predication does not evoke the same feeling of oddness that zeugma does, there is as far as I’m aware no label for the category that includes both phenomena. Since it would be helpful to have such a label, I’m going to appropriate copredication for that purpose, and when I need to refer to one of the two varieties, I’ll specify which one.

HAVING ESTABLISHED that copredication doesn’t necessarily cause incoherence, all that’s left of the court’s argument is the analogy between filled and kicked the bucket and keep and bear arms, and the judgment of grotesquerie. I don’t dispute that judgment, but the analogy doesn’t hold.

The court apparently thought that because both kick the bucket and bear arms in its military sense are idioms, the unacceptability of using filled and kicked the bucket to mean ‘filled the bucket and died’ compels the conclusion that it would have been similarly unacceptable in the Founding Era to use keep and bear arms to mean ‘keep weapons and serve in the militia.’ And that belief, in turn, presumably rested on the assumption that the idiomatic use of bear arms was constrained in the same way that the idiomatic use of kick the bucket is constrained today. But that assumption isn’t justified.

In order to understand why that’s so, it’s necessary to understand what it means to say that an expression is an idiom. As I said in an earlier post, an idiom is an expression whose meaning can’t be derived compositionally. In other words, the expression’s meaning isn’t simply a function of the meaning of its parts and of the way that they are syntactically combined. That’s clearly what Scalia meant in using the word, because what makes the military sense of bear arms an idiom is that its meaning can’t be derived from the separate meanings of bear and arms.

If you have any doubt on that point, keep in mind that if Justice Scalia had wanted to tell you the definition of idiom, he would have gone to Webster’s New International Dictionary, Second Edition, in which the relevant entry is as follows (my emphasis):

An expression established in the usage of a language, that is peculiar to itself either in grammatical construction (No, it wasn’t me) or in having a meaning which cannot be derived as a whole from the conjoined meanings of its elements (Monday week, that is, the Monday a week after next Monday; many a, that is, many taken distributively; had better, equivalent to might better; how are you?, that is, what is the state of your health or feelings?).

Now here’s the thing. The contrast between compositional meanings and idiomatic meanings isn’t a binary distinction between pure compositionality on one side and pure idiomaticity on the other. Rather, it’s a continuum, along which the relative degrees of compositionality and idiomaticity vary from one expression to another. (See the discussion of this in one of my earlier posts, which draws on the corpus data to illustrate the point.)

The fact that there are different gradations of idiomaticity comes into play when we think about the extent to which keep and bear_armsmilitary is or is not analogous to filled and kicked the bucket.

As an idiom, kick the bucket is at or near the extreme idiomatic end of the scale. It is almost impossible for us to figure how the meaning ‘die’ can be derived from a phrase whose compositional meaning is ‘move one’s leg so as to cause one’s foot to make forceful contact with a bucket.’ And there is no semantic or conceptual connection between dying and filling a bucket.

In contrast, the figurative use of arms in idiomatic bear arms was (and still is) semantically related to the literal use of arms as meaning ‘weapons.’ The relationship was one of METONYMY—the phenomenon in which a something is referred to, not by its specific name, but by the name of something that is closely associated with it, such as when the press is used as a way to refer to journalists and the work of journalism and when the White House is used as a way to refer to the president and their staff. The association between weapons on the one hand and military service and war on the other is obvious, and presumably would have been obvious during the 18th century as well, given that both senses were in common use.

That association would most likely have carried over to the idiomatic use of bear arms, and was probably strengthened by an association between that idiomatic use and the use of bear arms to mean ‘carry weapons.’ However, I suspect that the association was due more to the figurative use of arms than to the literal sense of bear arms. Because although for most of us today it is probably the literal sense that seems dominant (or primary, basic, central, what have you), that was probably not true of Americans in the late 18th century. Back then the idiomatic use was more frequent than the literal use, by an order of magnitude, and as a result the military sense of the phrase was probably experienced as being more salient. That probably would have been what bear arms first brought to mind and what would have been more significant culturally.

In light of the metonymic relationships I’ve been discussing, Heller’s analogy between keep and bear arms and filled and kicked the bucket doesn’t hold up.

More important, the metonymies that I’ve been discussing are relevant to the question of how keep and bear arms is likely to have been understood during the Founding Era.

Specifically, work in psycholinguistics and neurolinguistics suggests that when the text of the Second Amendment was read, the mental circuitry associated with both of the senses of arms and of bear arms was activated. The fact that bear arms was an idiom would probably have contributed to that activation as well, because when an idiom is read or heard, both the literal meanings of the words making up an idiom and the idiomatic meaning as a whole are generally activated.

Whatever the source of the activation, it would have occurred below the level of conscious awareness, but it would have played a role in the process leading to the reader’s fixing on a particular reading of keep and bear arms. And it’s likely that the activation of both the figurative and literal senses or arms would have been a necessary prerequisite to keep and bear arms being understood copredicatively, with arms being understood literally as part of the compositionally-derived phrase keep…arms but figuratively as part of the idiomatic phrase bear arms.

Update: I recently had an interesting and helpful conversation with Ted Gibson about the issues I’ve been discussing, and he suggested a simpler way to think about what makes filled and kicked the bucket seem so awful and about why keep and bear arms could have been more acceptable.

The problem with filled and kicked the bucket, Gibson suggests, is that conjoined phrases (e.g., A and B or This, that, and the other) generally combine expressions that are related in some way that’s relevant to the context, but when we read filled and kicked the bucket without any supporting context, there’s no apparent reason to think that dying has anything to do with filling a bucket. However, in a context in which there were a substantial-enough connection between the two, the phrase would be more acceptable.

It’s hard to come up with such a context for filled and kicked the bucket, but consider these vignettes, each of which ends with a phrase structurally similar to filled and kicked the bucket and keep and bear arms:

Chris had a small business selling paperback books door to door. She had no employees, so she had to do everything herself. She maintained a spreadsheet where she recorded all the money that came in and went out. So Chris both sold and kept the books.

One day Chris visited her friend Charles. The weather was beautiful: clear skies, pleasantly warm with low humidity, a little wind but not too much. So Chris and Charles went outside to enjoy and shoot the breeze.

While these come off as rather contrived (no surprise—they are contrived), they’re much more acceptable than the court’s example of filled and kicked the bucket.

Under an interpretation in which bear arms is understood idiomatically, the right to keep and bear arms could be seen as being analogous to the two vignettes (though without the need for the additional context) because the semantic relationship between the figurative meaning of arms and the literal meaning would presumably have apparent to 18th-century readers.

I’ll have more to say about the comprehension process in my next post. For now, my purpose in bringing it up has simply been to show that Heller’s analogy between filled and kicked the bucket and keep and bear arms was inapt.

For anyone who is interested, the following are some of the sources that informed the two paragraphs preceding the update: Klepousniotou et al., “Not all ambiguous words are created equal: An EEG investigation of homonymy and polysemy” (2012) (link); MacGregor et al., “Sustained meaning activation for polysemous but not homonymous words: Evidence from EEG” (2015) (link); Ortega-Andrés & Vicente, “Polysemy and co-predication” (2019) (link); Vulchanova et al., “Boon or Burden? The Role of Compositional Meaning in Figurative Language Processing and Acquisition” (2019) (link).

Once the argument based on filled and kicked the bucket is disposed of, there’s nothing left in the Heller opinion to justify the court’s insistence that arms couldn’t have meant two things at once.

Nevertheless, there are two arguments that would, if they were valid, provide the missing justification. The first would be that copredicative interpretations inherently conflict with principles of legal interpretation, on the ground that a single instance of a word can have only one meaning. The second would be that during the Founding Era, keep and bear arms could not have been understood in a way that depended on copredication.

However, I don’t think either of those arguments is valid. I will deal with the first argument in this post, and second in my next post.

—♦—

THE ACCEPTABILITY of copredicative interpretations in appropriate cases is established by three Supreme Court cases, which I will discuss in chronological order.

The first case is one that you may have heard of: District of Columbia v. Heller.

Although the members of the Heller majority didn’t realize it, their interpretation of bear arms is structurally parallel to the interpretation they rejected. In both, arms “[has] two different meanings at once: ‘weapons’ (as the object of ‘keep’) and (as the object of ‘bear’) one-half of an idiom.” Because while it’s true that the meaning of bear arms is idiomatic under the military interpretation, it is also idiomatic under the court’s interpretation, albeit to a lesser degree.

Recall that the court in Heller said that in the 18th century, bear meant ‘carry’ and arms meant ‘weapons.’ Both of those statements by the court are oversimplifications, as explained in my posts on bear and arms, but let’s accept them for now. Because if those are the separate meanings of bear and arms, the fully compositional meaning of bear arms would be ‘carry weapons.’

But that’s not what the court said bear arms meant. Rather, it said that “when used with ‘arms,’…the term has a meaning that refers to carrying for a particular purpose—confrontation.” More specifically, the court said that the “natural meaning” of bear in bear arms in the 18th century was “wear, bear, or carry upon the person or in the clothing or in a pocket, for the purpose of being armed and ready for offensive or defensive action in a case of conflict with another person.” (Ellipses in the opinion have been omitted.)

I’ve criticized that interpretation, but that criticism isn’t relevant to the present discussion; the issue I’m focusing on now isn’t whether the interpretation is correct but whether it is at least partly idiomatic. And the simple answer is yes: under the court’s interpretation the phrase bear arms means something different from the separate meanings of bear and arms. While ‘carry weapons’ is part of what bear arms means under the court’s interpretation, the limitation to carrying weapons only for a specific purpose doesn’t come from the separate meanings of the individual words. That means that under the court’s interpretation, bear arms in its military sense is partly compositional and partly idiomatic.

At this point I need to note that there is a possible complication, but ultimately it is a non-issue. The part of the Heller opinion I’ve been discussing purports to be interpreting only the word bear, not the phrase bear arms. But that is, as we lawyers like to say, a distinction without a difference. By the court’s own reasoning, bear means ‘carry [something ] for purposes of confrontation’ only in the phrase bear arms. But that being the case, ‘carry for the purposes of confrontation’ isn’t what bear means on its own.

Functionally, there’s no difference between saying on the one hand that bear has a special meaning when it appears in bear arms, and on the other hand that bear arms is at least partly idiomatic because the meaning of the phrase as a whole can’t be derived from the individual meanings of its components. Those are just different ways of describing the same phenomenon, and while most of us are accustomed to thinking of the basic units of meaning as being words, one of the insights that has emerged from corpus linguistics and corpus-based lexicography has been that in many cases, it makes more sense to focus on larger units, such as phrases.

LESS THAN A YEAR AFTER deciding Heller, the Supreme Court decided a case in which it interpreted a federal statute in a way that was indisputably copredicative. The case was United States v. Hayes, and like Heller it involved a restriction on owning firearms. It also happens to have been the case in which I first filed an amicus brief that drew on linguistics.

Hayes involved a federal statute that made it illegal for anyone who had been convicted of a “misdemeanor crime of domestic violence” (abbreviated MCDV) to own a firearm. At issue was how to interpret the statute’s definition of an MCDV:

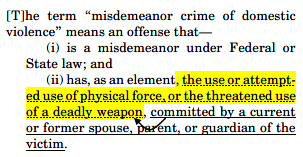

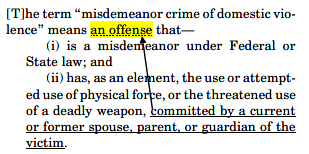

[The] term “misdemeanor crime of domestic violence” means an offense that—

(i) is a misdemeanor under Federal or State law; and

(ii) has, as an element, the use or attempted use of physical force, or the threatened use of a deadly weapon, committed by a current or former spouse, parent, or guardian of the victim.

The defendant, Randy Hayes, had been convicted in 1994 of committing battery under a statute that was not targeted specifically against domestic violence and that therefore applied whether or not the victim was the defendant’s “current or former spouse, parent, or guardian.” However, the victim had been the woman who was then his wife. Ten years later, police came to the Hayes’s house in response to a 911 call reporting domestic violence, and they discovered that he was in possession of a rifle. He was charged and convicted under the MCDV statute.

The issue before the Supreme Court was whether Hayes’s 1994 conviction had counted as an MCDV given that although he had been convicted of using physical force and his victim had been his wife, the statute he was convicted of violating did not specify such a family relationship as one of its elements. In other words, the government had been able to convict him in 1994 without having to prove that his victim had been his wife. Thus, the court was faced with two competing interpretations of the definition of misdemeanor crime of domestic violence. Under the interpretation that Hayes argued for, his prior conviction did not count as an MCDV because his marital relationship with the victim was not part of what the government had been required to prove in order to convict him. In contrast, the government argued that the 1994 conviction did amount to an MCDV, because Hayes’s victim had in fact been his wife.

The linguistic issue was whether on the one hand the relative clause “committed by a current or former spouse, parent, or guardian of the victim” modified the phrase that immediately preceded (“the use or attempted use….), as argued by Hayes and as shown below—

or whether on the other hand it modified “an offense,” as argued by the government—

What’s relevant for present purposes is that under the government’s interpretation, the provision was copredicative. Specifically, the phrase an offense means one thing as to clause (i) and something different as to clause (ii). With respect to clause (i)—an offense that is a misdemeanor—the word offense denotes a particular type of crime, while with respect to clause (ii)—an offense that…committed by—it denotes a specific instance of such a crime (in technical terms, a TOKEN of the type). My brief flagged this, but didn’t offer an opinion as to whether it was likely to affect how the provision would be understood.

On the broader issue of how the statute’s language would ordinarily be understood, my brief supported the defendant’s interpretation—a position that was based entirely on the linguistic issues. But the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the government, with Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Scalia dissenting. Thus, the Supreme Court interpreted the statute in a way that made it copredicative. This is clear from the following statement by court (paragraph breaks added for clarity; my comments in curly brackets):

Most sensibly read, … [the statute] defines “misdemeanor crime of domestic violence” as a misdemeanor offense that (1) “has, as an element {TYPE interpretation}, the use [of force],” and (2) is committed {TOKEN interpretation} by a person who has a specified domestic relationship with the victim.

Now, I don’t think any of the Justices realized that the majority’s interpretation had this consequence. Nothing in either the majority opinion or the dissent reflecting any awareness of the issue. And although the issue was mentioned in my brief, that reference was on page 36 (out of 38), and if anyone actually read that far, their eyes might have glazed over by that point.

THIS BRINGS US to the third case that’s relevant to whether copredicative interpretations can be acceptable: United States v. Davis, a Supreme Court case that was decided a month ago.

Davis involved a statute that was similar in its structure to the one in Hayes. The statute is 18 U.S. Code section 924(c), which provides that if anyone uses or carries a firearm “during and in relation to a crime of violence or drug trafficking crime,” they are subject to a mandatory sentence of at least 5 years in addition to the penalty for the underlying crime.

At issue in Davis was the statute’s definition of a “crime of violence”:

For purposes of this subsection the term “crime of violence” means an offense that is a felony and—

(A) has as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person or property of another, or

(B) that by its nature, involves a substantial risk that physical force against the person or property of another may be used in the course of committing the offense.

It was a given that subparagraph (A), with its reference to the “element[s] of the offense,” calls for a TYPE; interpretation; the issue to be decided was whether subparagraph (B) similarly called for such an interpretation, or instead called for a TOKEN interpretation. Under the latter alternative, the definition would be copredicative in essentially the same way as in Hayes.

This time the choice between the two readings was presented to the court explicitly (though without using the terminology of copredication). The government argued in favor of the copredicative alternative, and it pointed to Hayes as support for its argument that such an interpretation was permissible.

The court ruled that a copredicative interpretation was not warranted with respect to the statute at issue, but all nine justices agreed that copredicative interpretations are permissible in appropriate cases (though they didn’t use that terminology). The four dissenting justices—Kavanaugh, Roberts, Thomas, and Alito—favored the copredicative interpretation, and in support of that argument they relied on Hayes. And although the majority disagreed, it didn’t reject the idea of such an interpretation altogether: “It’s possible for surrounding text to make clear that ‘offense’ carries a double meaning. But absent evidence to the contrary, we presume the term is being used consistently.”

While Davis makes explicit what was implicit in Heller and Hayes—that copredicative interpretations are permissible in appropriate circumstances—it remains uncertain what it would take for the court to conclude in a specific case that such an interpretation would be justified. On the one hand, Davis says that the context must “make [it] clear that [the word at issue] carries a double meaning,” but on the other hand it indicates that the presumption of consistent usage can be overcome by “evidence to the contrary,” without specifying how strong the evidence must be.

More importantly, Davis and Hayes point in opposite directions on that issue, because on purely linguistic grounds the justification for a copredicative interpretation was weaker in Hayes than it was in Davis. The most obvious difference between the two provisions is that in the statute at issue in Davis, it is clear beyond doubt that subparagraph (B) modifies “an offense” and that it is grammatically independent of subparagraph (A), while in the statute at issue in Hayes, the phrase “committed by a [family member] of the victim” is more naturally read as modifying the verb phrase that immediately precedes it (“the use or attempted use of physical force, or the threatened use of a deadly weapon”). For the details, I refer you to my amicus brief in Hayes and Chief Justice Roberts’s dissenting opinion.

Cross-posted on Language Log.